History is littered with products that fail to meet expectations in the marketplace. Observers often depict such failures as technology for technology’s sake, the proof that innovation should start with a need (market pull) rather than with technology (technology push).

‘Technology push’ is an innovation approach that often gets a bad reputation for making clunky or unsuitable products, because it sets out to make a product by taking a technology and finding a possible need it can satisfy. However, the problem usually stems from failing to do the second part properly – often by overlooking whether the hypothetical need actually exists for real users, or by also failing to satisfy a genuine need.

Google Glass is a great example. The concept was launched to initial excitement with a futuristic proposition as to how it could be your next inseparable bit of tech for all sorts of use cases.

However, in the cold light of day many felt that the needs being met were minor improvements over smartphone life and they couldn’t justify the device, its cost, the user’s appearance wearing it, and its impact on the privacy of the user and those nearby. When the initial launch scaled back the functionality from the proposition offered in the unveiling video, even fewer needs were met, dooming the product from day one. A product without a purpose will never succeed.

A pure market pull approach, where there isn’t a suitable technical implementation, is even more hopeless … but we rarely get to see the results. A technology without a need can still reach the market with blind backing, while a product without a viable technology will usually fail at the prototype stage. All that reaches the public is a ‘concept car’ visual of a product that sounds really cool… and then it disappears without a trace. Technology push gets its bad reputation because its failures are a much more public affair.

In practice, technology push can work just as well as market pull if a suitable need and proposition are found, and the product is built around this proposition with a good user-centred design. And there are clear examples of technology push success.

Dyson’s surprise entry into the hand dryer industry in 2006 was driven by a search for new applications for the company’s expertise in high-performance, low-cost, high pressure air blowers. Their technology push was coupled with a careful search for unmet needs, and great execution developing a product to satisfy it – quickly capturing a huge chunk of what had been considered a mature market.

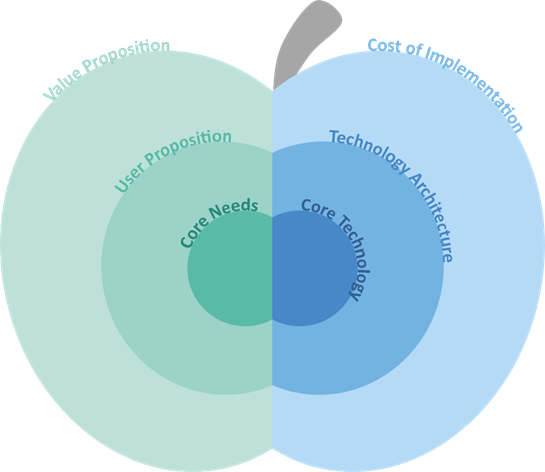

To succeed it is important to use a balanced approach, building both sides of what we call the Innovation Apple; in parallel building a convincing proposition around one or more core needs, while also building a viable technical execution around one or more core technologies.

he Innovation Apple encourages balanced focus between the need, or proposition, and the technical implementation during development of new innovations

The core issue

At a basic level you need a way of meeting the core need; that is the core technology. But to be embraced by users, the whole technology architecture must deliver on an appealing user proposition.

And finally, for the concept to work commercially, you need to build the Innovation Apple such that the value proposition justifies the cost of implementation. Whether an idea starts as a technology or as a need, it is wise to complete both sides of the core of the apple as quickly as possible; what you learn in the process for one side will shape the other.

The core technology will define the performance at meeting the core need(s); where the technology architecture will determine usability performance (such as battery life); and the cost of implementation as a whole decides whether it can be marketed at an appropriate price, and therefore support a valid business case.

Therefore, both the user and value proposition will depend not only on the need being met, but how well this is met in reality by the product.

For example, there is a need for rapidly chilling a packaged beverage (can or bottle) to give the proposition of reducing the space and energy spent on refrigerated drink storage in shops and cafés.

We might be tempted to say we have a user proposition, where a consumer selects a beverage from a shelf at ambient temperature and takes it to the till to be cooled while paying for it. However, the proposition will strongly depend on the cooling performance, so we would first explore the core technology we might rely on. In doing this, we find a number of different approaches available.

But we also find that even applying the most extreme technical solutions offered by current technology, it still takes around a minute to chill a single can, and longer for bottles, since further cooling will just build a wall of ice on the inside of the package, leaving the middle warm.

This delay shapes the proposition, as it may be too long to wait at the till, compared with the convenience of ready cooled drinks.

Now we have completed the core of the Innovation Apple, we can then do one of three things:

- Look for propositions that might work with the achievable cooling rates e.g. rapid chilling to restock a smaller fridge

- Shift focus to perform basic research into new faster cooling methods

- Carefully note the technical performance that would be required to fulfil our proposition, and park the idea, pending the arrival of new technologies

At the end of the day, a product sinks or swims on its proposition – not just how strong it is, but also how well it is delivered.

Balancing the risks

Innovative product development can be a risky business. Whether an innovation starts as a technical idea looking for an application or a market need looking for a solution those risks are best managed with a holistic view of both needs and implementation challenges.

The Innovation Apple encourages innovators to bring the market and technology components of this process into balance, maximising chances of success.