Last year, France became the first country in Europe to implement a repairability index across five categories of electronic devices. This included smartphones, laptops, televisions, washing machines and lawnmowers. The index assesses a range of different criteria like documentation, disassembly, availability of spare parts, price of spare parts and other product-specific aspects.

Later in the year, the UK’s new ‘Right to Repair’ law was introduced. The new law legally requires manufacturers to make spare parts available to both consumers and third-party companies within 2 years of a product’s launch. Depending on the part, these must be made available for a minimum of 7 or 10 years. The legislation aims to extend the life cycle of a range of devices and appliances.

More recently, Apple has announced ‘Self Service Repair’, an initiative to ensure individual Apple parts, tools, and manuals (starting with iPhone 12 and iPhone 13) will be made available to all individual consumers and repair shops.

Evidently, it’s a busy time for repairability – so what’s next?

How does design play a part in product development?

Although both France’s repairability index and the UK’s right-to-repair law are a good step forward, they are only a small part of the solution required to overcome this challenge. Inspiring consumers to fix their broken products is key, and importantly repairing a product if it’s broken needs to be a more desirable option than simply buying a new one.

This is where design comes in. It’s our responsibility to ensure that end-users of all ages and backgrounds have both the tools and the motivation to change their own behaviour and embrace repairability to the full.

The repairability of a product is almost always determined during the design phase. The design decisions that are made at this phase will have a significant impact on whether a product is repaired or replaced.

Over 80% of all product related environmental impacts are determined during the design phase of a product.”

Frugal Innovation: How to do more with less by Radjou/Pranhu

Below, I have attempted to categorise what I believe to be the 5 most important considerations to make when designing for repairability.

1. Durability

Perhaps the best way to ensure that your product is repaired is to ensure that it is built to last. There is little point repairing something that won’t be able to withstand its extended life. Furthermore, something that is physically durable may not even have to be repaired in the first place.

Think about how the product is going to be used and the environment that it is going to be used in. This will help to inform the materials and manufacturing processes most suitable to use. If you can, perform accelerated life testing, subjecting your product to conditions in excess of what will be expected in normal service. This will help expose potential faults and modes of failure and allow you to design in solutions around them, before the product goes to market.

When we talk about durability, we might immediately think about the physical durability of a product, like a rugged phone case or power tool. However, durability exists in multiple forms. Another of which is the emotional durability of a product. Put simply, a product must chime with the user, as most of the battle is getting the user to want to repair their product in the first place. This is covered in more detail later.

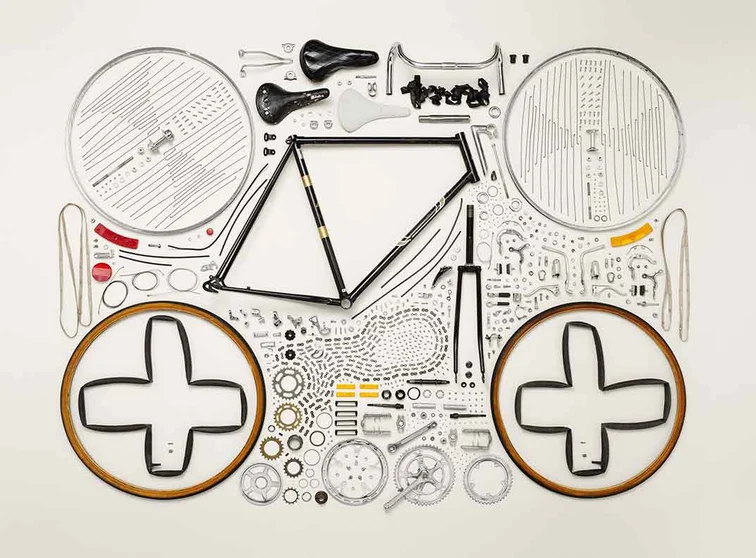

2. Disassembly

It may sound obvious, but a product that can easily and safely come apart is more likely to be repaired than one that cannot. Try to avoid using any tamper-proof fixings and stick to industry standards where possible. Don’t use glue or weld anything that may need to come apart further down the line. Lastly, ensure that everyday household tools, or even better, no tools at all are required in order to disassemble the product.

However, being able to disassemble a product is fine, providing that when your product has been broken down, it can be serviced, maintained and spare parts are made available to the consumer.

Image: 1980’s Raleigh Bicycle, Photo by Todd McLellan

3. Modularity

A product that is made up of distinct and easy-to-replace modules has a lot of benefits. Empowering users to be able to easily replace a broken or outdated module (e.g. the battery in a Framework Laptop – pictured below) is not only convenient from a repairability perspective. It can often help build consumer confidence and reassurance over time.

Furthermore, a modular product doesn’t just help to facilitate repairability. Modularity can help to enable a product to be upgraded. Imagine that you’ve had your laptop for 5 years and since then, technology has advanced so that a new battery is now available that enables a 50% longer battery life. This could be an attractive prospect for someone potentially thinking that their existing product may have reached the end of its life.

As the world changes ever more quickly – the environment, fashion, trends, lifestyles – so do our needs, wants, and requirements. If the products that we own can’t mould and adapt to our rapidly changing lifestyles, our motivation to hold onto and repair products will diminish. Whether modularity is used to help ensure that something can be easily repaired, upgraded, or adapted to our lives, it will certainly help to ensure that we keep them for longer.

Image: Framework laptop

4. Emotion

Why do we throw certain products away and what stops us from choosing to go down the repair route rather than replace? A lot of it comes down to whether we have an emotional attachment to the products we use.

The way that a product makes us feel has a big part to play when it comes to repairability. Unfortunately, our current throw-away society fuelled by the affluent and consumerist culture that surrounds us is anything but emotional.

What makes us hold onto that wobbly old chair or tatty pair of jeans that we always wear? The products that we use on a day-to-day basis talk to us through the way they look or the memories that they hold.

The good news is that once you have taken the leap and made that first repair, it’s often at this point that a real emotional attachment can be formed. Repairing your possessions can build an emotional attachment and discourage from simply throwing something away and replacing it.

Understanding the product user relationship

We all have relationships with the products that we use, and the desire to throw away a product could be symptomatic of a failed relationship. For a product to be sustainable (and therefore not disposable) the user must have empathy with the product. Hence why a tatty old pair of jeans is emotionally durable, because the user establishes a relationship with the product – and brand – which evolves over time. User-centred design is a tool that aims to uncover the deep-rooted needs and desires of a user to inform the design of products that add real value to their lives.

The Zippo lighter is a good example of an emotionally durable product. It’s a quality, well-made item with a quirky yet satisfying mechanism. If something makes you smile every time you use it, it’s likely that you will never become bored with it.

Image: Pexels – Zippo lighter designed by George G. Blaisdell

The objects in our lives are more than mere material possessions. We take pride in them, not necessarily because we are showing off our wealth or status, but because of the meanings they bring to our lives. A person’s most beloved objects may be inexpensive trinkets or frayed furniture that are torn or faded.” – D. Norman (2004)

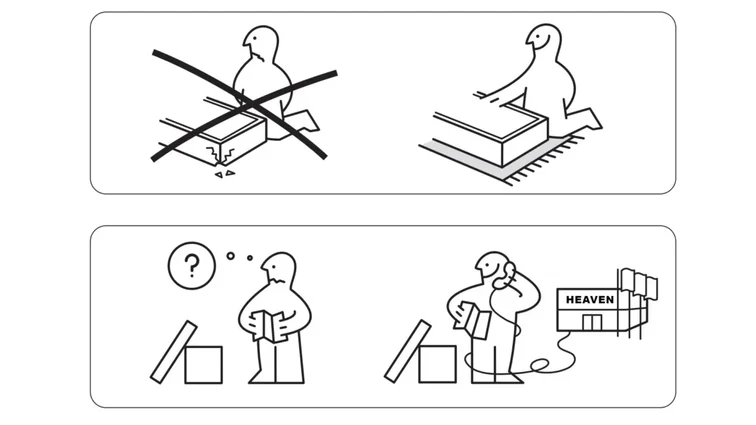

5. Communication

Design doesn’t stop at the point of sale or use. It’s important that designers use their voice beyond the initial design of a product to ensure that effective and inclusive documentation is made available to educate users on repair. Effective communication of how to facilitate the repair process for a product should be treated as just as important as the design of the product itself, not an afterthought.

Small things like iconography and illustrations to indicate how to dismantle something, or colours and shapes to help ensure the user knows where components belong are key.

Lastly, why not provide a repair service and aftersales support for your customers and repair their broken products for them? Ensuring a product is technically repairable is one thing, but the service around repair is equally as important.

Image: IKEA Instructions

Summary

Sustainable design often has a tendency to focus on the symptoms of environmental damage rather than the root cause. Consequently, understanding the actual drivers that underpin human consumption and the waste of products are often overlooked.

In this article I have highlighted 5 considerations that every designer should make when designing for repairability. Importantly, ensuring your product is repairable is not just as simple as using accessible fixings and throwing in a repair manual. Repairability is about understanding and changing the way your product makes the user feel. It’s about building trust and emotional attachment to the products we own.

Furthermore, selling something that is repairable is not only better for the environment, but often a better commercial proposition too. Keeping your customer for longer gains their trust and helps to build brand loyalty. It’s worth remembering that a repair service and/or spare parts can also be a healthy revenue stream.

Make sustainability part of the business plan

Repairability means a multitude of things from durability to modularity to serviceability. Each should be given serious consideration when designing new products. At 42T, our design processes ensure that the environmental impact of a product is central to how we work.

We’ve used these considerations to design durable and repairable products for our clients. This has helped to ensure their customers have products that are built to last, that will become a better return on investment, be more sustainable, and bring joy every moment they’re used.