Making any product sustainable can be difficult. Unlike the term ‘organic’ there is no set of strict criteria that products must meet before this term is applied. So, it’s up to designers and manufacturers to navigate this field to improve their products and manufacturing methods.

To make the largest impact when changing a product, there must be a deep understanding of each stage of its life. This means not simply having knowledge of raw materials, but also recognising that the way in which the users interact with the product can change the overall impact significantly. This is where lifecycle assessment (LCA) methodologies come in.

LCA methodologies

A full lifecycle assessment can be a very complex and expensive study. The activities that need to be carried out are governed by ISO 14044:2006 and need to be verified by an expert. In many cases this process takes a vast amount of time and resource to complete. However, to make a claim about a product or process’ impact on the environment this type of study is required. The benefit, however, is that the assessment provides a deep understanding of a product which can be published and built on by others.

Despite the difficulties and complexities involved with a full study, several elements and aspects of the process of conducting a LCA can be beneficial to the design stage of product development. This can be done without incurring the cost and time penalty if no marketing claims are required. To determine which parts of an LCA could be used for product design, an understanding of the different steps is required.

What is involved with an LCA?

- Scope

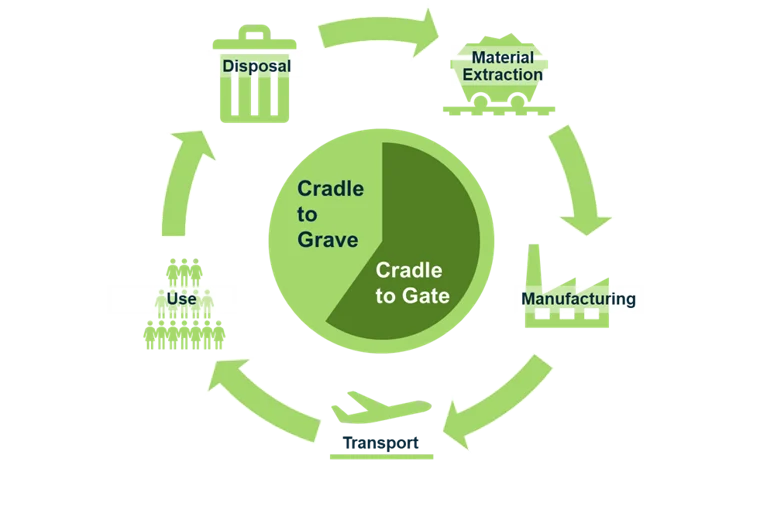

Possibly the most important part of the LCA is determining what the system boundaries are. Also, which part of the product life will be examined. Two common terms often used are cradle-to-gate and cradle-to-grave. The former describes all processes from raw material extraction to when the product reaches distribution to the user. The latter includes the entire process all the way through until product disposal and waste processing.

- Functional units

The functional unit is particularly important when comparing the results of LCAs of similar products with each other. For example, the functional unit for a water bottle would likely be the volume of water it could contain. This functional unit would mean that water bottles of different sizes could then be compared against one another.

- Data collection

Any LCA is only as good as the data that is used to create it. There are two main data types: data measured from the process being analysed and data from a reference database. The first type is always preferable. Although this data collection is where most of the difficulty and expense in a full LCA arises, and may not always be possible as this often requires the full co-operation of suppliers. The other data option, data from reference sources, is becoming more widely available as more data is constantly added. The main caveat to using reference data is that for an LCA to provide useful outputs it must be shown that the data used is comparable to the process being analysed.

- Quantifying the damage to the environment or cost

Once the data has been collected and the emissions from each stage of the process are known, they are converted to relative figures that allow certain types of emissions to be compared. One of the most well-known of these is kg/CO2 equivalent, or global warming potential relative to that of CO2. Using this, the damage implications that the product will have on the planet and human health over a certain time can be estimated.

So, what would a stripped back LCA for product design look like?

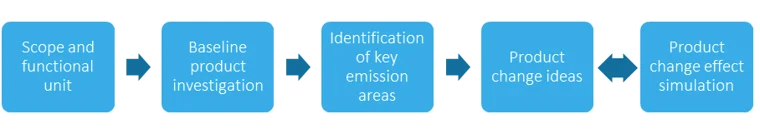

To improve a product, there must first be something to compare against – a baseline. This could be a previous version of a product or a product from a competitor. The scope and functional units of both the baseline and the product being examined should be the same to ensure they are both fully comparable. It should also establish the emission types that the design activity will be trying to reduce.

Once the scope has been determined, the flows of materials into and out of the different processes can be estimated. As a stripped back LCA is attempting to reduce the cost and effort of a full study, this will rely heavily on existing data sets.

The investigation into material flows should indicate where emissions are being generated. Also, in what quantities throughout the life of the product. It is here that designers can make the biggest changes to the impact of the product.

Equipped with the knowledge of the emissions sources and scales, the product can be changed to mitigate them. This could include changing the raw material of the packaging or changing the number of products that can be transported by a single plane by the way in which they tesselate together. Or it could involve changing the amount of each product that makes a unit.

All these changes can be simulated when the process is changed in the LCA to establish the scale of the change and if there are any other repercussions that follow these alterations.

What are the limitations of this approach?

- Using LCA methods rather than conducting a full peer-reviewed study can save considerable time and expense. Not having a study prevents any marketing claims from being made as to the improvements that have been achieved. A full LCA could be conducted on the product once the manufacturing process was online, if a marketing claim was desirable, still reducing the product development time and cost of experimenting with different sustainable design options.

- The results of any investigation using LCA methods is only as good as the assumptions made. The source that the reference date is collected from needs to be comparable to the processes that are likely to be used. For instance, sourcing raw materials from the same geographical location and forming products of the same material of a similar size and production scale.

- There is additional cost and time associated with adding this analysis to product development. A stripped back approach limits this. But will still add time and effort to the product development process compared to design without the additional considerations. There is also the cost associated with gaining access to high quality data from other LCAs for the decision-making process.

- Any LCA methods rely on communication and information being forthcoming from suppliers. It’s almost impossible to estimate the impact of processes without information on the inputs and outputs of their processes.

What’s happening out in the real world

One of the more well-known LCAs conducted was that performed by Levis. They discovered that a large percentage of the emissions from their jeans were from the washing process. Jeans are constrained by what is currently in fashion and seasonal trends.

Design decisions like dyeing jeans slightly darker to show dirt less, meaning less frequent washing, could be options that designers could make to reduce environmental impact.

Other examples include a study on beer production and consumption in the UK that concluded that beer in steel cans has the lowest impact and bottled beer the worst.

And also a TetraPak portal where they collated sponsored research on the environmental impact of food and drinks packaging. They looked at areas such as cartons and PET bottles, refillable vs non-refillable containers, and paper vs plastic materials.

Where to from here

LCA methodologies provide a framework and process for designers and product manufacturers to systematically reduce the emissions associated with their products. They also enable designers to simulate the effects of their changes on the overall life of the product.

42T’s product design processes are underpinned by a serious consideration of the product’s environmental impact – from manufacture through to disposal. We would be delighted to explore how the methodologies discussed here might benefit your own product design.